Learn More

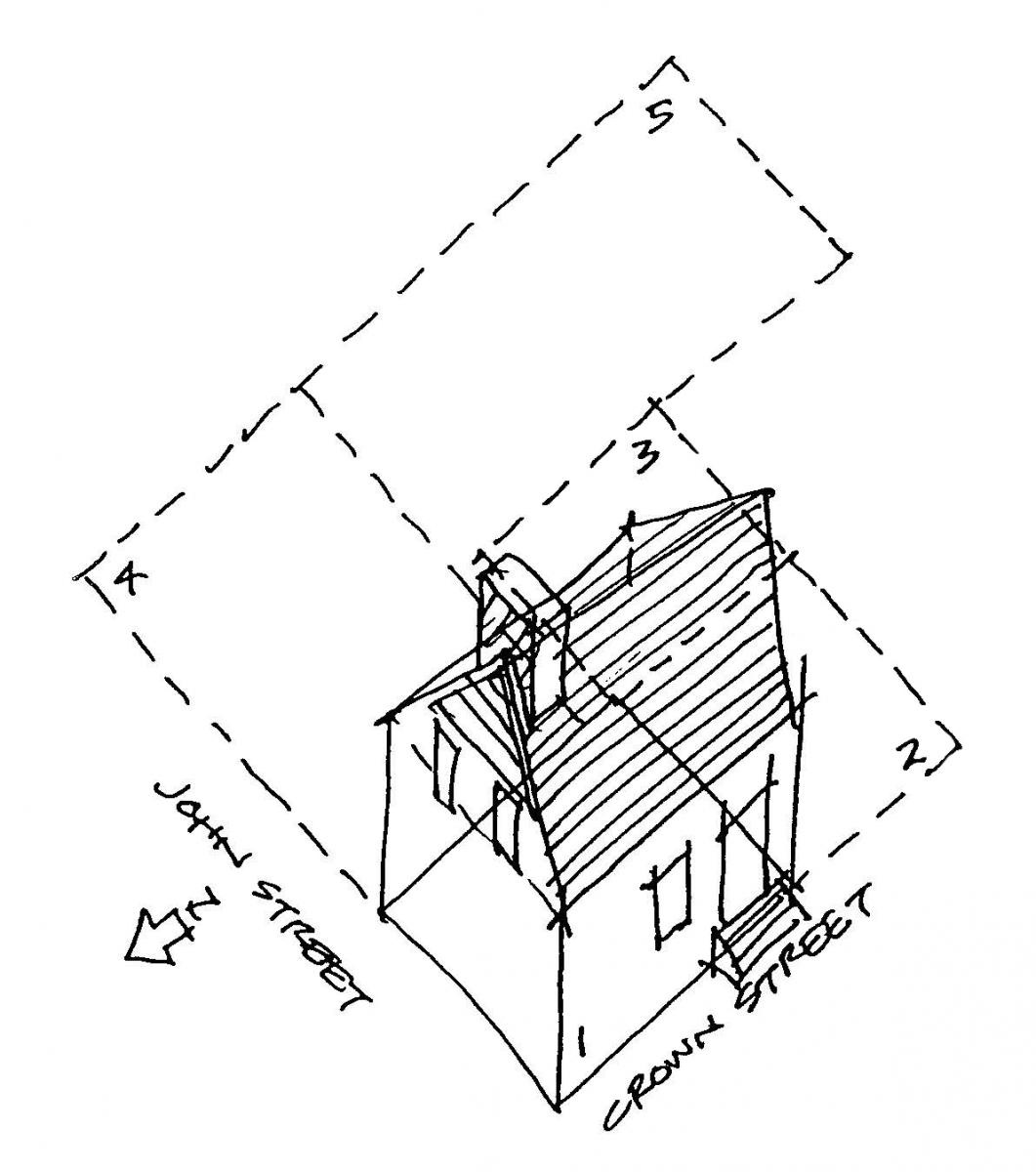

Phase 1 (c.1661-1669) Downstairs

Entrance Halls

The original footprint of Phase 1 was a simple utilitarian structure with a single central room over a basement. The peaked roof would have also been used as a loft above for additional storage space. When the English conquered New Netherland in 1664 this change in government also ushered in changes to social and architectural taste. The interior walls and doorways separating the front door to create an “entrance hall” were probably added sometime in the 1670s and reflect this transformative period. Entrance halls were very fashionable in England at that time, and so, as English culture spread to this former Dutch colony, some people began adding these halls to give their homes a more trendy, modern feel.

Entrance halls have long been used as components of several architectural styles, but their popularity has varied over time and across cultures. Greek and Roman architects used them to separate the outside world from the private spaces within while informing the symmetry of structures. Medieval castles and manor houses in Europe also typically had entryways or gatehouses as a means of defense.

During Europe’s Renaissance period entrance halls again became popular in residential architecture. Renewed interest in classical learning led to the incorporation of entrance halls on homes and palaces in the form of grand foyers and vestibules. The most extravagant of these featured elaborate decorations and detail. In this way the entrance hall came to represent wealth and high social status.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, entrance halls had become a standard feature of many residential buildings in the United States and Europe. With the rise of the middle class and increased focus on domestic comfort and privacy, entrance halls became more functional and less ornate, serving as a transitional space between the public and private areas of the home.

Esopus Wars

The Esopus Wars were a series of conflicts that took place between Dutch colonists and the Esopus tribe of the Lenape people in the mid-17th century. “The Esopus” is a term used in historical records to describe both the Dutch community around Wiltwyck (now Kingston) as well as the native people of the broader region. From what we know in surviving accounts, the Esopus Wars were waged across much of the lowlands of modern Ulster County.

The first Esopus War erupted following several years of rising tensions between the original inhabitants of the Esopus and Dutch colonists who had begun living and farming in the vicinity in the 1650s. These rising tensions precipitated the construction of a Stockade at Wiltwyck on the orders of Peter Stuyvesant in 1658. The ambush and murder of several native men on the evening of September 20th, 1659 was the event that ultimately touched off almost a year of ensuing violence and destruction only resolved by a peace treaty made on July 15, 1660.

This peace, while it endured, was unsatisfactory and failed to resolve many of the issues that had fomented the war in the first place. The Esopus tribe, seeing no other way to rectify their increasingly precarious regional status, broke the peace with a surprise attack on Wiltwyck and the new community at Hurley in the middle of the day on June 7, 1663. It was this attack in which the Persen House was burned along with the rest of the stockade.

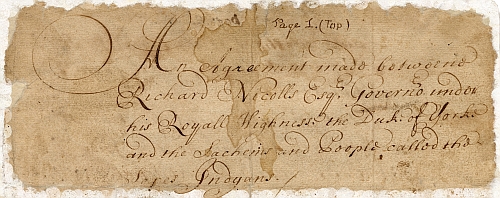

A final peace would not be achieved until a council was held at New Amsterdam in May of 1664 in which representatives of the Dutch Colony met with an array of Tribal representatives from across the Hudson Valley. The peace adopted there was followed by a treaty made with the new English Governor Richard Nicolls at Esopus on October 7, 1665.

The myriad causes that contributed to the Esopus Wars, and the destruction and displacement of the native people of the region that occurred as a result, offer stark testament to the often tragic results of European settlement and conquest in the Hudson Valley during the Colonial period.

Additional Resources:

- Teacher Resource: The Story of the Esopus Natives and their Encounter with European Colonialism Curriculum Guide

- Nicolls/Esopus Peace Treaty of 1665

- Interview with Edwin M. Ford, City of Kingston Historian (2017)

- Journal of the Second Esopus War by Capt. Martin Kregier. With an account of the Massacre at Wildwyck (now Kingston) the names of those killed, wounded, and taken prisoners, by the Indians on that occasion. 1663 (original manuscript), 1910 (printed version translated from the original Dutch), 2021 (digital edition). https://archive.org/details/JournalOfTheEsopusWar/

- Ruttenber, E. M. (1992). Indian tribes of Hudson's River to 1700 (Vol. I). Hope Farm Press. (Available to view in the Archives Reference Library at the Ulster County Records Center, 300 Foxhall Ave., Kingston)

Root Cellars

Phase 1 of the Persen House was built with functionality in mind, and every floor of the building served a task that contributed to the survival and comfort of the people living there. Below the main floor of phase one is a basement space that would have originally been utilized as a root cellar to keep certain types of food fresh for extended periods of time. In this way the entire lowest level of the house served a similar role to a modern kitchen refrigerator.

Root cellars, set below ground level, offered a shaded and temperature-regulated space which would have remained above freezing and below 50°F for much of the year. These conditions were ideal to store and keep things like potatoes, carrots, and turnips year-round for the family to eat. It is important to remember that their main source of food was whatever could be grown in the summer months, supplemented by hunting and domesticated livestock. Whatever was grown needed to last throughout the Winter, and food kept in a root cellar would have been used to feed both family and livestock for months at a time.

Barber-Surgeons and the Van Imbroch Family

Gysbert Van Imbroch was the first medical professional in Wiltwyck, working as the community’s barber surgeon. He lived in the original version of Phase 1 with his wife Rachel and their three children. As a barber surgeon, Gysbert would have been responsible for everything from the typical grooming responsibilities of a modern barber to more unusual practices like bloodletting, setting bones, wound treatment, and surgical procedures.

While the combination of these two professions seems absurd by modern standards, the barber surgeon arose out of a need among monks in the Middle Ages to have a trained person at the monastery capable of maintaining tonsures (a specific hairstyle). The requirements of the job and the accompanying expensive and precise cutting instruments meant that necessity broadened the barber’s responsibilities over time to include other tasks where a sharp knife and steady hand were invaluable. By the renaissance, the trade of barber surgeon was a well-defined and integral profession in communities throughout Europe, and they were often relied on for many of a community’s medical needs, with a physician only occasionally offering advice or overseeing courses of treatment.

Gysbert’s life at Wiltwyck was tumultuous and short. On June 7, 1663 a surprise raid destroyed the stockade in an attack that initiated what is now known as the Second Espous War. As the community burned over a dozen women and children, including Rachel Van Imbroch, were taken as captives by the Esopus and marched south towards modern-day Napanoch. Rachel remarkably managed to escape and evade recapture, arriving back at the ruins of the stockade with valuable information about the other captives. Legend tells that the unnamed woman who led the armed search party to find the other captives was none other than Rachel, but no surviving source names her definitively.

Rachel died in 1664, followed by Gysbert in 1665. Upon Gysbert’s death an inventory was made of his estate by the court at Wiltwyck. This inventory, an invaluable document of early life and material culture at Wiltwyck, survives today in the archives of the Ulster County Clerk’s Office and illustrates his extensive library and educational background. Included in the inventory are many of the tools which Gysbert would have employed in the treatment of the wounded and sick people of this rough frontier community.

Learn more about Gysbert's Inventory.

Additional Resources:

- Teacher Resource: Wiltwyck: A look at Life in a Dutch 17th Century Ulster County Town Curriculum Guide

FEATURE: Fireplace

In the original wood structure, the fireplace would have been located where the mantelpiece is leaning against the wall in the picture above. However, the fireplace was moved to its current location circa 1669 when the second phase was added. Fireplaces and chimneys served as important structural pieces, so one possible reason why this one was moved was to create structural symmetry with the new fireplace in Phase 2.

FEATURE: Hinges and Hardware

Original cast iron hardware on doors in colonial houses is a significant feature of the architectural and historical heritage of the country, representing the craftsmanship and durability of the colonial era. These hardware pieces, including door knobs, hinges, locks, and latches, were typically handcrafted and designed to withstand the test of time, and they have remained as a testament to the ingenuity and creativity of the early American artisans who created them. Today, these original cast iron hardware pieces are highly valued by homeowners, collectors, and preservationists, as they offer a glimpse into the past and contribute to the unique character and charm of colonial homes.