<< Previous Room on the Tour - Phase 5

Learn More

Phase 4 (c. 1735-1849) Upstairs

Revolutionary War Taverns

Taverns played a significant role in the social and economic development of the American colonies. They served as community gathering places, centers of commerce, and important sources of news and information. They were central to the social life of the colonies. They served as meeting places for political groups, such as the Sons of Liberty, and as venues for civic functions like town meetings. Taverns were also popular spots for entertainment and leisure, offering card games, music, and dancing.

Taverns also served important commercial functions. They were often located on major trade routes, making them ideal locations for travelers to stop and rest, providing food and lodging, as well as stables for horses and wagons. Tavern owners commonly served as postmasters and provided mail delivery services to patrons. Many also served as local officials, such as road commissioners, tax collectors and other various public offices.

Colonial taverns were typically large, multi-room buildings. The main room, known as the taproom or barroom, was the heart of the tavern. It was where customers gathered to socialize, drink, and eat. The taproom was usually furnished with a bar, stools, tables, and chairs.

Taverns also had private rooms for dining and lodging. The dining room was often furnished with tables and chairs, while the bedrooms had simple beds and furnishings. The kitchen was usually located in the rear of the tavern and was equipped with a large hearth and cooking utensils.

Today, many historic taverns still exist and serve as reminders of America's colonial past.

Courtesy of www.frauncestavernmuseum.org.

Additional Resources:

- Earle, Alice Morse. Stage-Coach and Tavern Days. Internet Archive. New York: Macmillan Co., 1905. https://archive.org/details/stagecoachtavern00earluoft.

New York's Founding Fathers

Text here

Additional Resources:

- Student Activity Packet: Voting for Kids

- Kingston's Buried Treasures Lecture: "Ulster County Courthouse: Birthplace of New York State by Paul O'Neill - April 19, 2013"

- Kingston's Buried Treasures Lecture: "John Jay: Model of Diplomacy by Professor Ray Raymond Director of the Institute of Constitutional Studies at SUNY Ulster - January 16, 2015"

- Kingston's Buried Treasures Lecture: "NYS Constitutional Convention: The Foundation for a Nation by Judge Albert Rosenblatt - November 13, 2015"

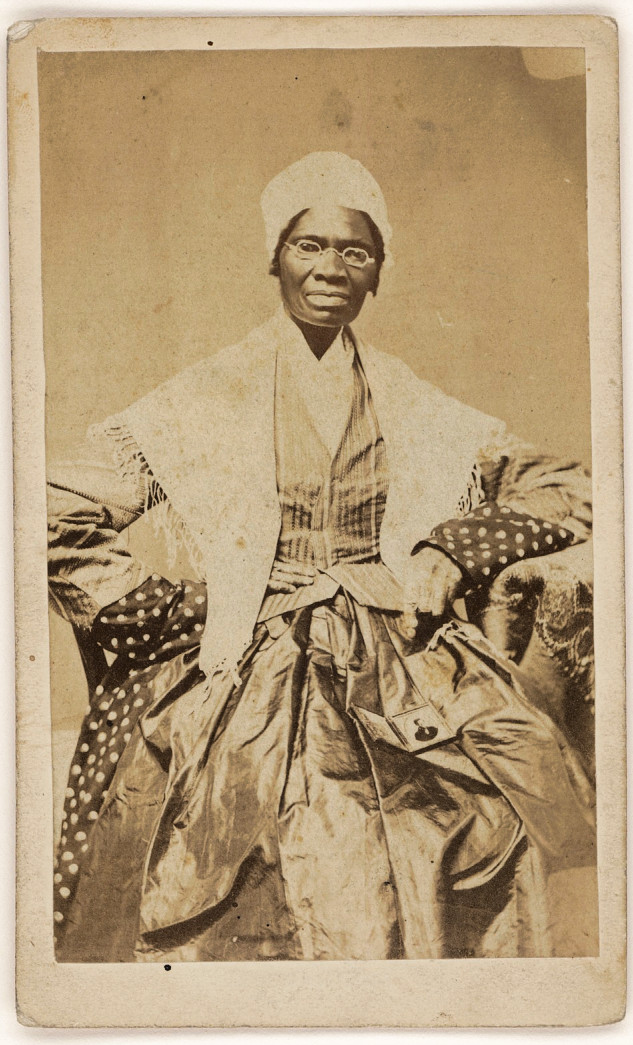

Sojourner Truth

Special thanks to Ulster County Commissioner of Jurors Paul O'Neill for the information provided in this section. "Carte de visite image of Sojourner Truth" c. 1866. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture via Wikimedia Commons.

"Carte de visite image of Sojourner Truth" c. 1866. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture via Wikimedia Commons.

Born into slavery in Rifton, New York around 1797, Sojourner Truth (or Isabella, as she was then known) toiled in servitude for the next 29 years. By 1825 she found herself bound to John Dumont in the Town of New Paltz. That year she made an agreement with Dumont guaranteeing her freedom, and that of her family, on July 4, 1826 - one year earlier than the date set for statewide abolition - provided she “did well and remained faithful.” By July, however, John Dumont had reneged on his part of the agreement, refusing to free her as promised. So, Isabella, with her infant daughter in tow, left the Dumont property and walked to the home of Isaac Van Wagenen, who welcomed her and her daughter.

However, she had been forced to leave her son, Peter, behind with the Dumonts. John Dumont shortly thereafter sold Peter, who eventually ended up with Solomon Gedney, who in turn sold Peter to his brother-in-law in Alabama - a sale illegal in New York due to the impending abolition of slavery. When the Gedneys refused to return Peter to New York and to his mother, Isabella took her case to the steps of the Ulster County Courthouse.

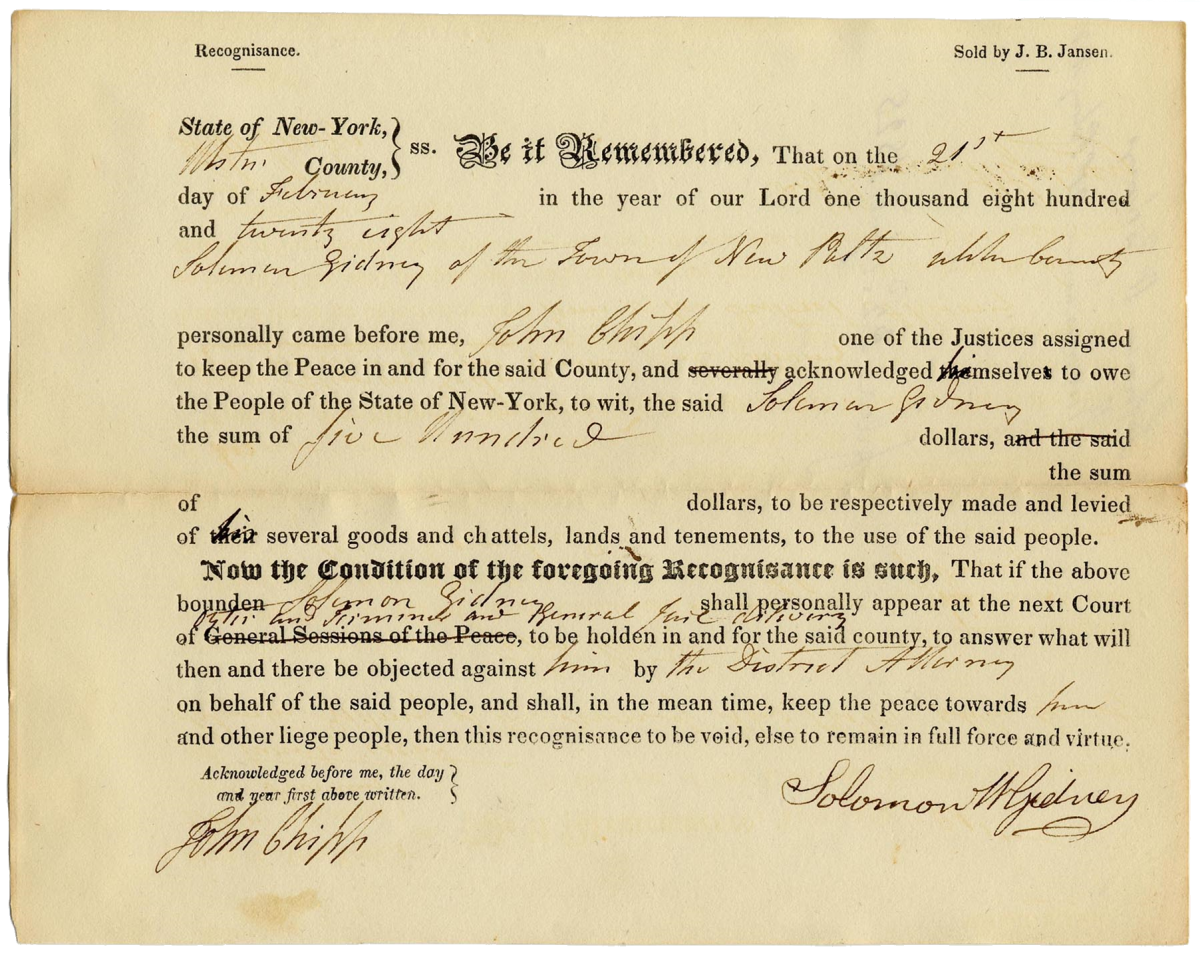

Below is the actual Recognizance Bond issued February 21, 1828 requiring that Solomon Gedney appear before the court. The subsequent order of Judge Abraham Bruyn Hasbrouck dated March 14, 1828 directed that “the said boy Peter be and he is hereby discharged from the control custody and direction of the said Solomon W. Gedney”, thus releasing Peter to his mother. This landmark case marks the first time a black woman sued a white man – and won.

Almost overnight, Isabella became a national figure and noted speaker, abolitionist and one of our earliest Women’s Rights Activists. And in 1843, already a noted abolitionist, she changed her name to “Sojourner Truth”, the name by which we know her today.

Transcription:

State of New York,

Ulster County, SS.

Be it remembered, that on the 21st day of February in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and twenty eight Solomon Gidney of the Town of New Paltz Ulster County personally came before me, John Chipp one of the Justices assigned to keep the Peace in and for said County, and acknowledged himself to owe the People of the State of New-York, to wit, the said Solomon Gidney the sum of Five hundred dollars, to be respectively made and levied of his several goods and chattels, lands and tenements, to the use of the said people.

Now the condition of the foregoing Recognisance is such, That if the above bounden Solomon Gidney shall personally appear at the next Court of Oyer and Terminer and General Jail delivery, to be holden in and for the said county, to answer what will then and there be objected against him by the District Attorney on behalf of the said people, and shall, in the mean time, keep the peace towards him and other liege people, then this recognizance to be void, else to remain in full force and virtue.

Acknowledged before me, the day and year first above written.

John Chipp Solomon Gidney

Additional Resources:

- New York State Archives Digital Collections: People v. Solomon Gedney (Writ of habeas corpus and related documents)

- Kingston's Buried Treasures Lecture: "Sojourner Truth: Ulster County's Voice of Freedom by Anne Gordon - November 16, 2012"

- There are many biographies and books on Sojourner Truth. The Archives Reference Library at the Record Center has the following in hardcopy for researcher use:

- Bernard, Jacqueline. (1967). Journey Toward Freedom; The Story of Sojourner Truth. Dell Publication.

- Ferris, Jeri & Hanson, Peter E. (1991). Walking the Road to Freedom: A Story about Sojourner Truth. Carolrhoda Books.

- Gilbert, Olive & Truth, Sojourner. (1997). Narrative of Sojourner Truth. Dover Publications Inc.

- Koester, Nancy. (2023). We Will Be Free: The Life and Faith of Sojourner Truth. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

- Krass, Peter. (2005). Sojourner Truth: Antislavery Activist. Chelsea House.

- McKissack, P. C., & McKissack, F. (1994). Sojourner truth: Ain't I A Woman? Scholastic.

- Shumate, Jane. (1992). Sojourner truth and The Voice of Freedom. Millbrook Press.

- Whalin, W. T. (1997). Sojourner Truth: American Abolitionist. Barbour & Co.

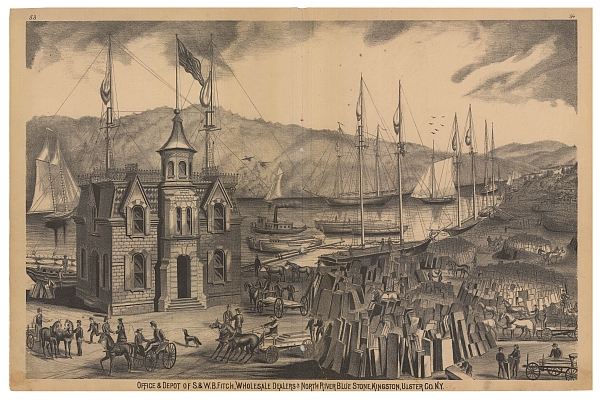

Hudson River Bluestone

Hudson River Bluestone is a type of natural stone that is found along the banks of the Hudson River in New York State. It is a type of sandstone that is characterized by its blue-gray color and fine grain. The stone was formed during the Devonian period, which was over 350 million years ago, when the area was covered by a shallow sea. Over time, layers of sediment built up and were compressed into the dense, hard stone that we see today.

Hudson River Bluestone has been quarried for centuries, and has been used for a variety of purposes including building construction, landscaping, and paving. The stone is highly valued for its durability, strength, and natural beauty. It was widely used in New York City during the 19th and early 20th centuries for a variety of construction projects. Some of the most notable uses of Hudson River Bluestone in New York City include:

-

Sidewalks: Hudson River Bluestone was a popular choice for sidewalks throughout the city due to its durability and resistance to wear and tear.

-

Bridges: The stone was also used in the construction of several prominent bridges in the city, including the Brooklyn Bridge and the George Washington Bridge.

-

Buildings: Hudson River Bluestone was often used as a facing material for buildings, particularly in the downtown Manhattan area. The stone's unique color and texture made it a popular choice for high-end commercial and residential buildings.

-

Paving: The stone was used extensively for paving streets, particularly in the downtown area. It was an ideal choice for heavily trafficked streets.

Overall, Hudson River Bluestone played a significant role in the construction of New York City's built environment and continues to be a popular choice for outdoor features and interior design elements today. It is often used for patios, walkways, retaining walls, and other outdoor features, in addition to interior flooring and wall cladding.

Additional Information & Resources:

- Teacher Resource: The Builders of Ulster County: A Curriculum on the History of Immigration

- Friends of Historic Kingston: Bluestone History is Part of Kingston

- Kingston's Buried Treasures Lecture: "Ezra Fitch: Founder of Abercrombie & Fitch by Edwin Ford - February 15, 2013"

- Kingston's Buried Treasures Lecture: "Kingston's Bluestone Industry: The Rock that Paved a Nation by Dr. Peter Roberts - December 13, 2013"

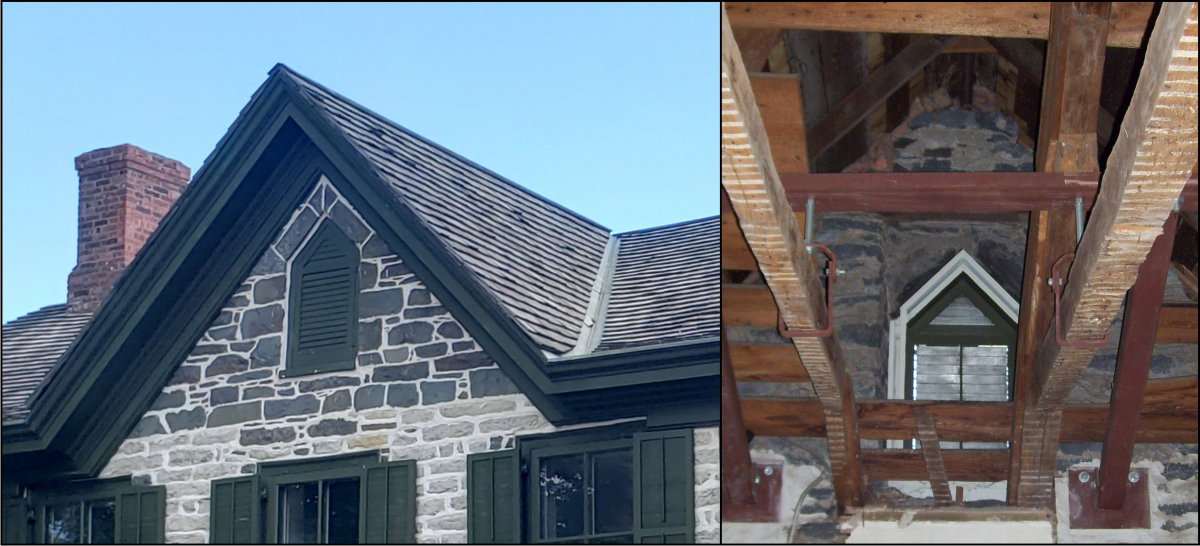

Bluestone Gables & the Gothic Revival

On the John Street-facing wall of Phase 4 is a gable constructed of beautiful bluestone. Note the clear distinction between the dark bluestone and original limestone. This gable, and another like it in Phase 1, are not part of the house’s original structure, but were added sometime in the 1800s. The 19th century saw a booming bluestone industry in Ulster County, and so it was not uncommon for people to construct bluestone additions for their houses.

In his report, architect Kenneth Barricklo states, "The exterior of the phase one, two, three, and four building appears to have remained virtually unchanged from 1777 to circa 1850. With the Gothic Revival style, that began with the great industrial and commercial expansion in the Hudson valley, ending the colonial period, many stone houses in Kingston and elsewhere were "modernized" with stone gable ended dormers and decorative wood trim...Along with the change of style from the earlier Dutch to the newer Gothic revival came the removal of earlier hung hand-hewn wood gutters at all roof eaves and their replacement with new built-in boxed gutters, concealed within a new cornice and frieze detail that became the new roof edge."

The Gothic Revival is an architectural style that emerged in the late 18th century and became popular throughout the 19th century, particularly in Europe and North America. It is characterized by the use of medieval Gothic architectural elements, such as pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and buttresses, as well as the incorporation of ornamental details such as tracery, pinnacles, and gargoyles. The Gothic Revival was seen as a romantic and nostalgic movement that sought to revive the grandeur and beauty of the medieval past, and it had a significant influence on Victorian-era architecture.

Additional Information:

- The Archives Reference Library at the Record Center has the following in hardcopy for researcher use:

- Reynolds, Helen Wilkinson. Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley before 1776. Payson and Clarke Ltd., New York: 1929.

- Stevens, John R. Dutch Vernacular Architecture in North America, 1640-1830. West Hurley, NY: Society for the Preservation of Hudson Valley Vernacular Architecture, 2005.

-

Hudson-Mohawk Vernacular Architecture, Formerly The Dutch Barn Preservation Society (DBPS), incorporating The Society for the Preservation of Hudson Valley Vernacular Architecture (HVVA)