An Introduction

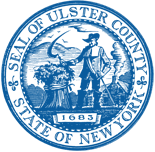

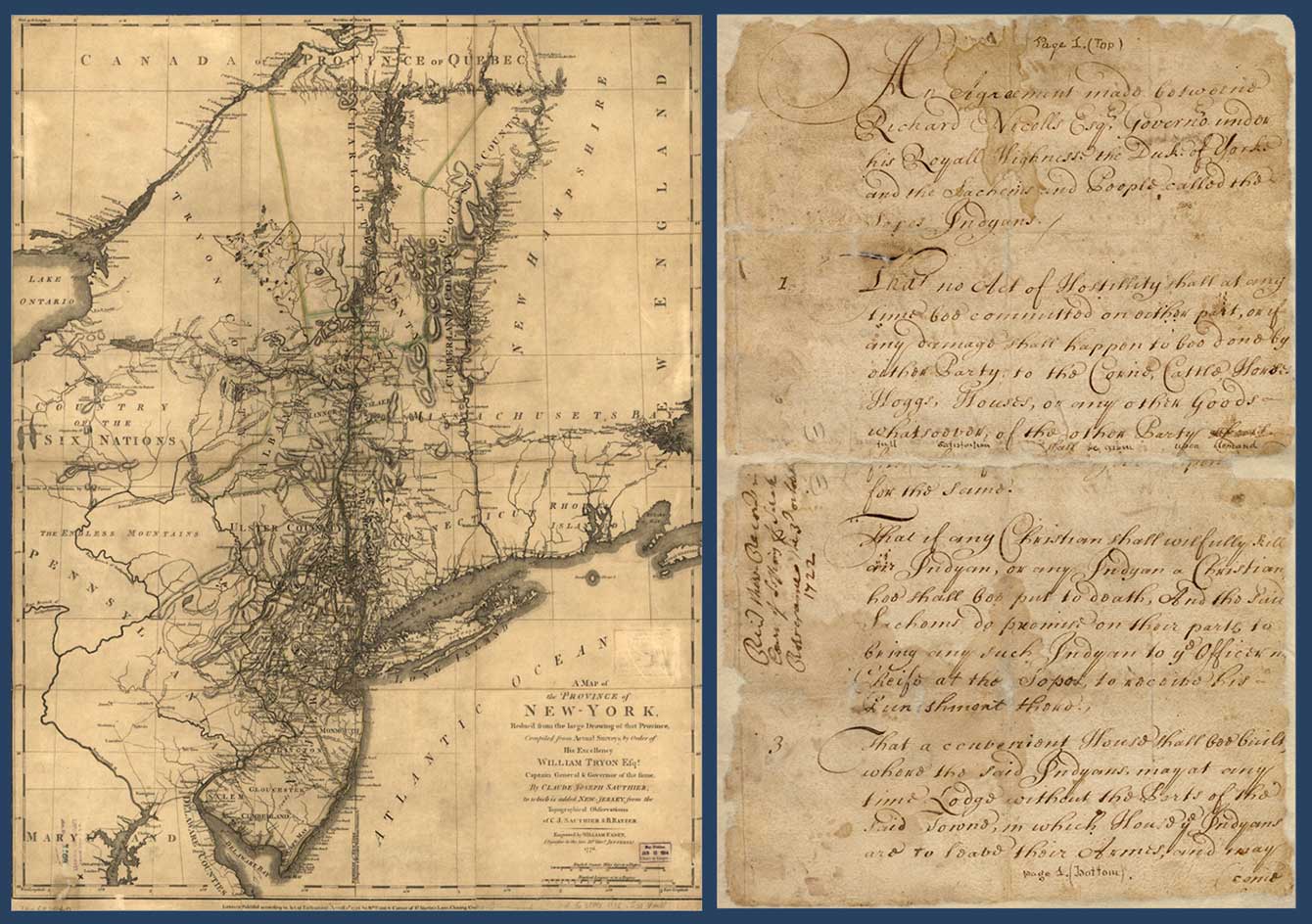

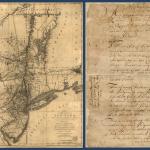

The date is October 7, 1665. The exact location is unclear from the records, but likely, you are standing either in Kingston, or in Fort James in New York City. (Both locations can be seen on the map shown here. Fort James is not labeled, but an image of a fort is located on the tip of the island of Manhattan. This is Fort James.). Members of the new ruling class of New Netherlands, now renamed New York, assembled with leaders of various Native American tribes. Present at this gathering were the following individuals: Richard Nicolls, Jeremias Van Renslaer, Philip Pietersen Schuyler, Robert Nedham, S. Salisbury, Edward Sackville, Onackatin, Waposhequiqua, Sewakonama, and Shewatin. These ten men signed the Treaty that you will see here. This Treaty ended various conflicts that had arisen since 1659, when the First Esopus War had occurred.

Image: Novae Belgiae Angliae nec non parties Virginiae multis locis emendate (circa 1685) by Nicolaes Visscher. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/97683561/.

An Introduction, continued

The First Esopus War lasted from 1659 until 1660, and even though there was peace, tensions still ran high. The Second Esopus War started in 1663, as natives were upset by the continued Dutch encroachment on their lands. The war ended in 1664 and was concluded with a treaty at Fort Amsterdam in New York City on May 16, 1664. However, on August 27, 1664, New Netherlands was taken over by the English and became New York. The first colonial governor of New York was Richard Nicolls, who had served with the Duke of York’s father during the English Civil War and was an ardent Royalist. As the now Governor of New York, Richard Nicolls set about instituting changes, notably in many of the civil laws of the colony. Nicolls was responsible for instituting English reforms like trial by jury, and requiring all landowners to apply for new patents from the English Duke of York. Part of Nicolls duties of consolidating authority under the new English system was to negotiate a new peace with the Native Americans. In the 1665 Nicolls/Esopus Peace Treaty, violence between the English and the Native Americans was prohibited and, should violence occur, a prescription for justice was included.

The Treaty also encouraged future renewals of the peace and requested the young people be brought for these renewals so that the peace would be maintained in future generations. The Nicolls/Esopus Peace Treaty was renewed thirteen times (that we know to date) between 1665 and 1745. Notably, Richard Nicolls was the only colonial governor to sign either the original Treaty or any of the Renewals. The painting to the right of the map, called The Treaty of Penn with the Indians by Benjamin West, depicts a treaty signing between the English and the Lenape, of which the Esopus were a part. Might this scene be similar to the one on October 7, 1665? While we don’t know for certain, images such as this one help us to imagine what it might have been like.

Image: The Treaty of Penn with the Indians (circa 1771-1772) by Benjamin West. By Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=817244

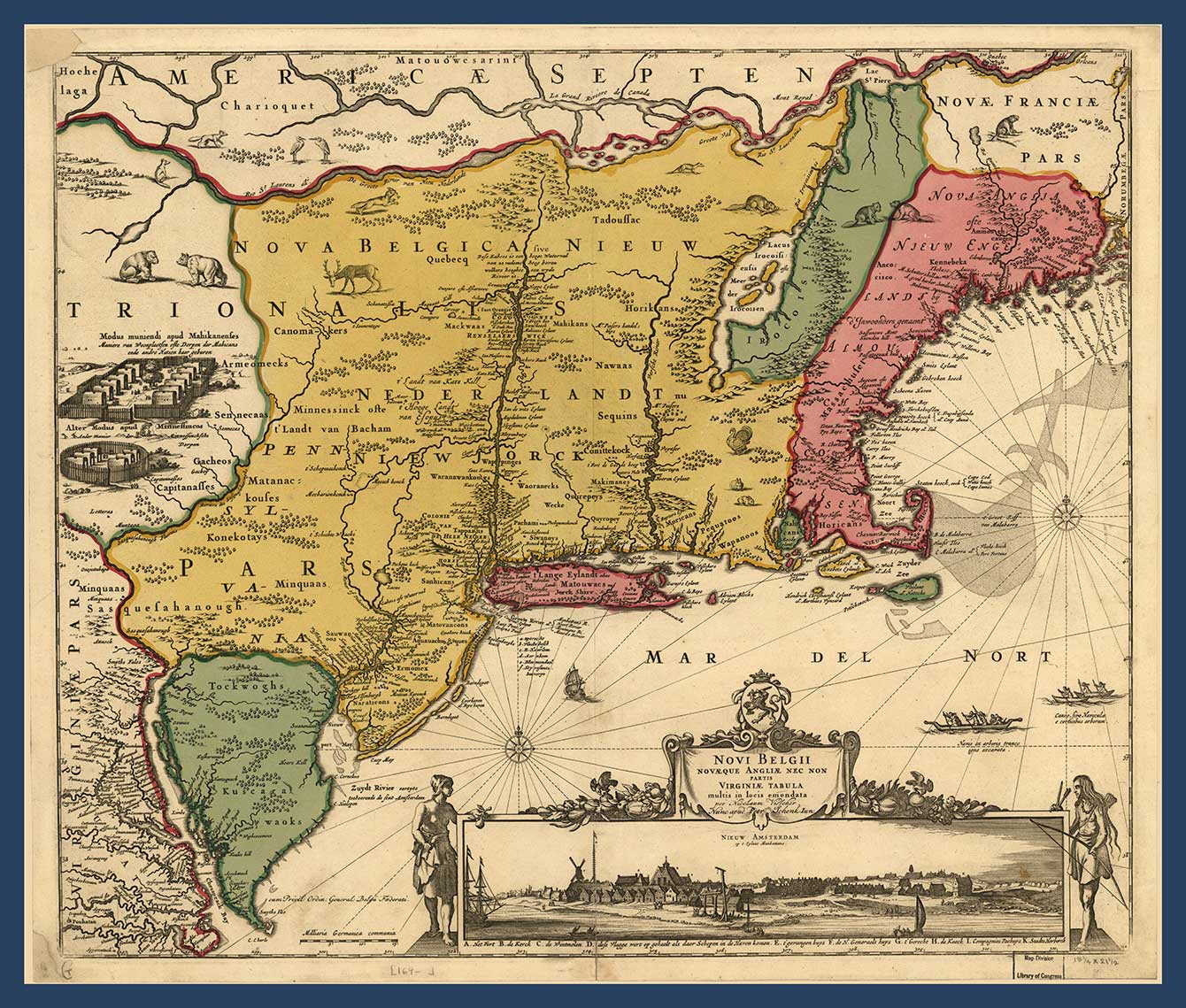

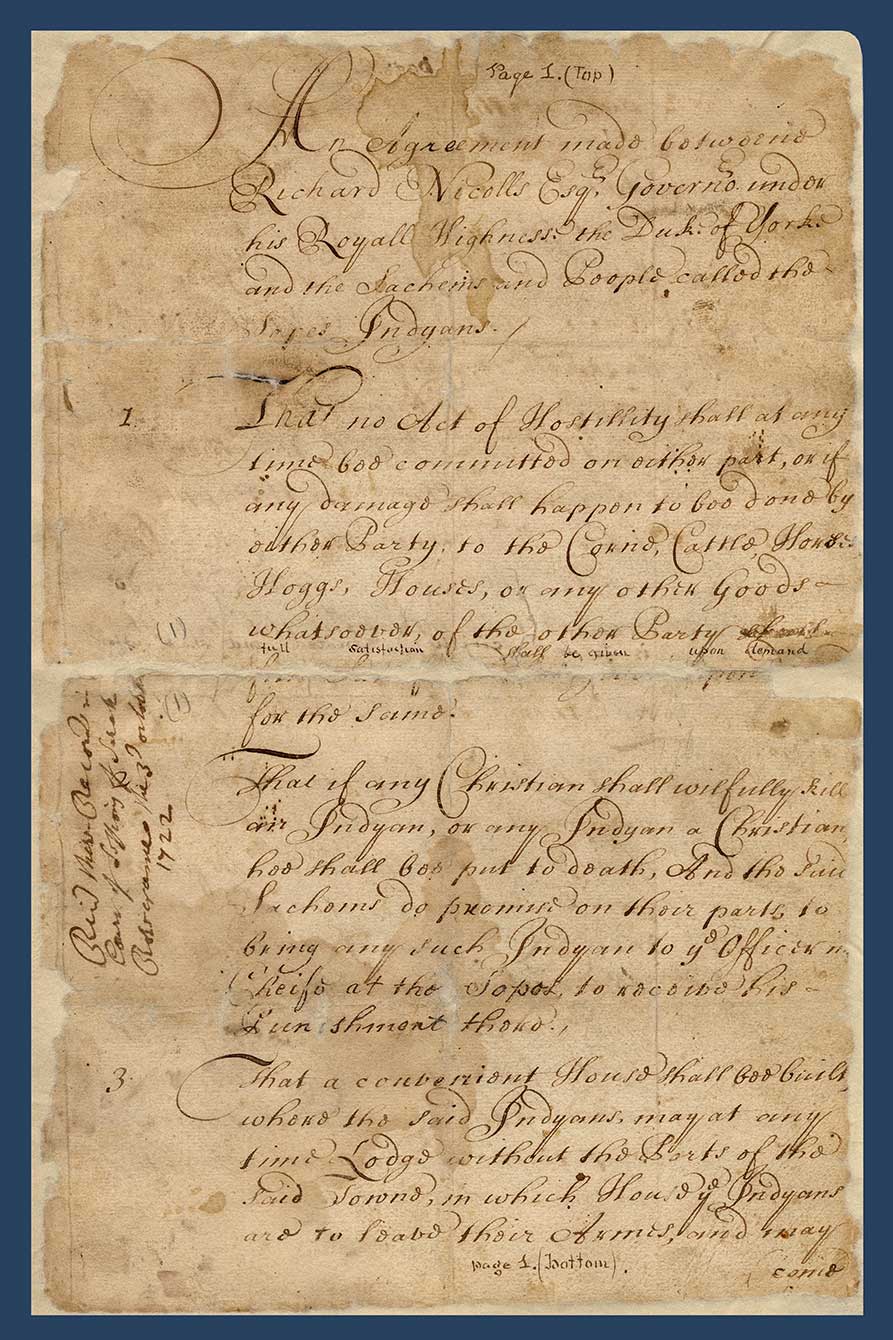

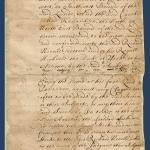

1665 Nicolls Esopus Peace Treaty, Page 1

“no Act of Hostility shall at any time be committed on either part”

The original Peace Treaty and all the Renewals through 1681 are bound together in a booklet.

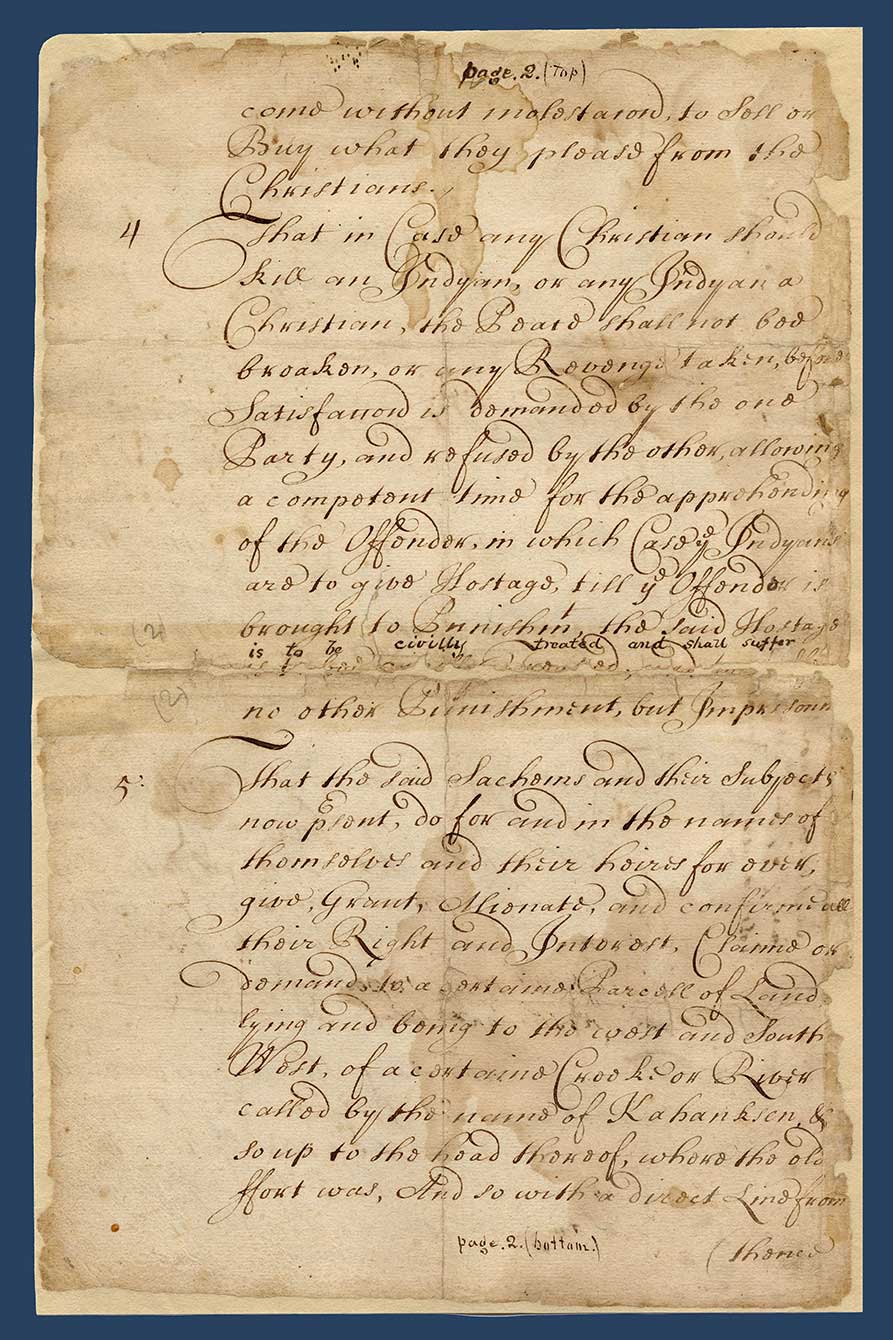

1665 Nicolls Esopus Peace Treaty, Page 2

“the Peace shall not bee broaken or any Revenge taken”

1665 Nicolls Esopus Peace Treaty, Page 3

"And in the name of the Indyans their Subjects one of the Subjects, do deliver two other round Small Sticks in token of their assent to the said agreement"

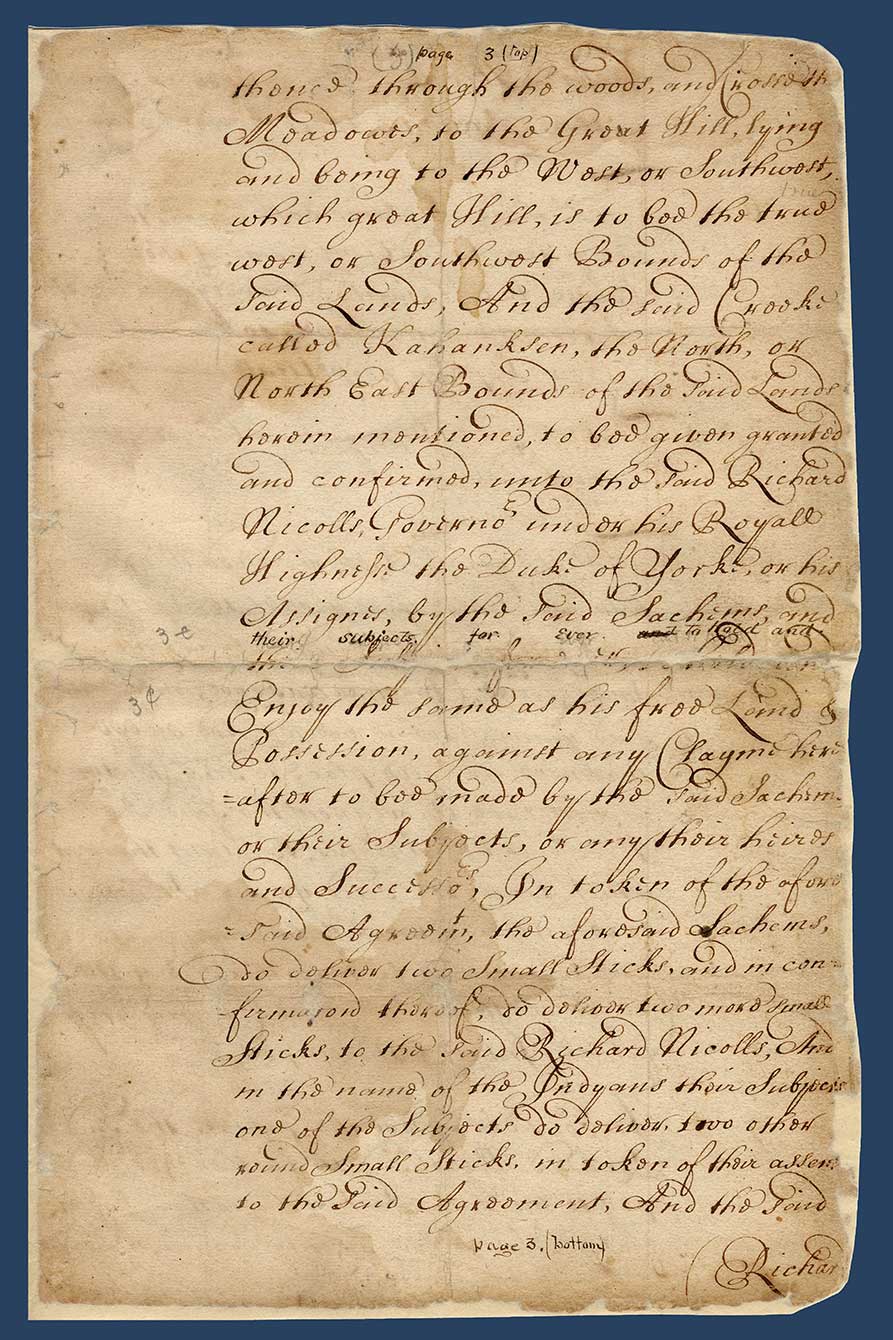

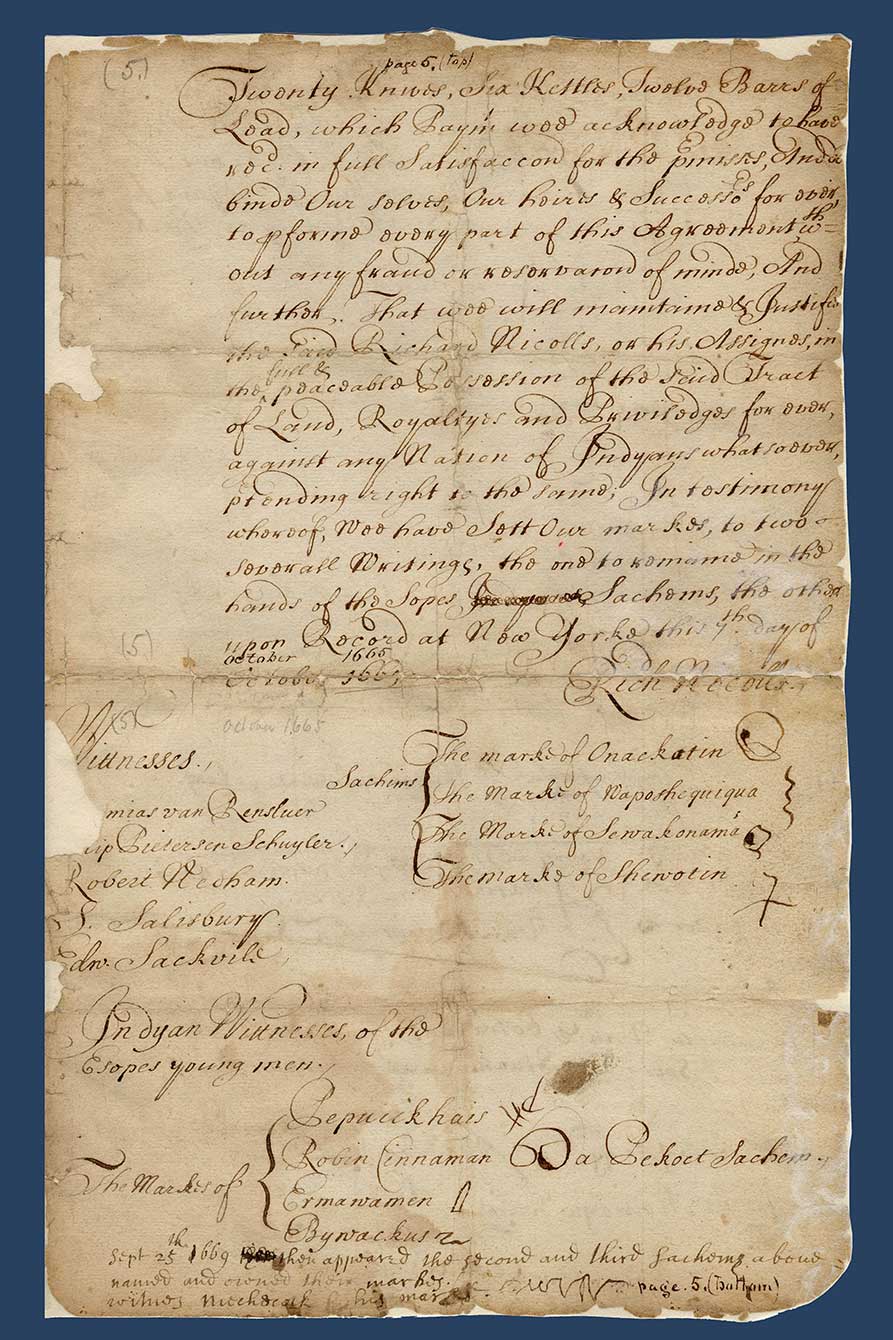

1665 Nicolls Esopus Peace Treaty, Page 4

“all past Injuryes are buryed and forgotten on both sides”

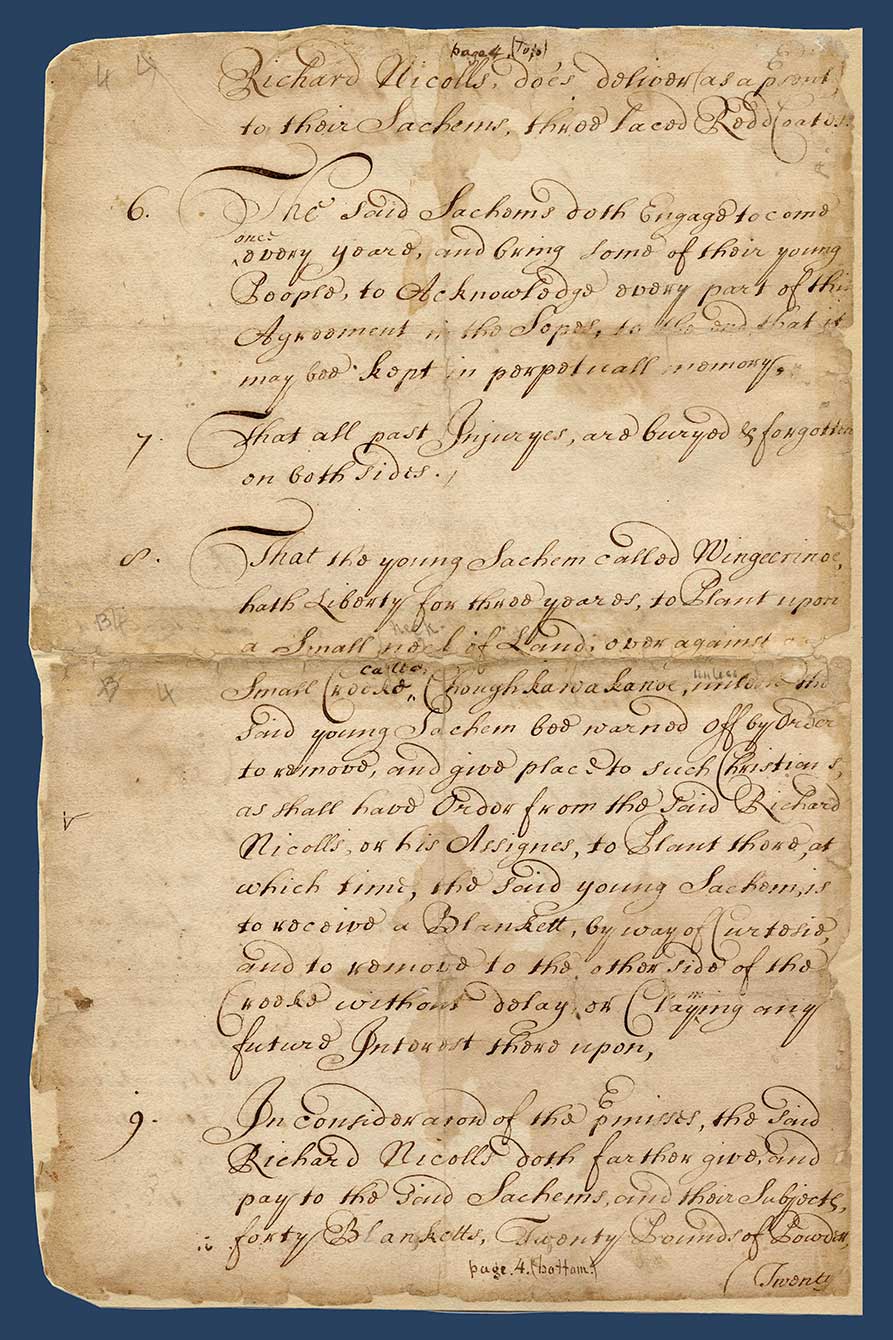

1665 Nicolls Esopus Peace Treaty, Page 5

"In testimony whereof wee have Sett our markes to two severall writings, the one to remain in the hands of the Sopes Sachems, the other upon Record at New Yorke"

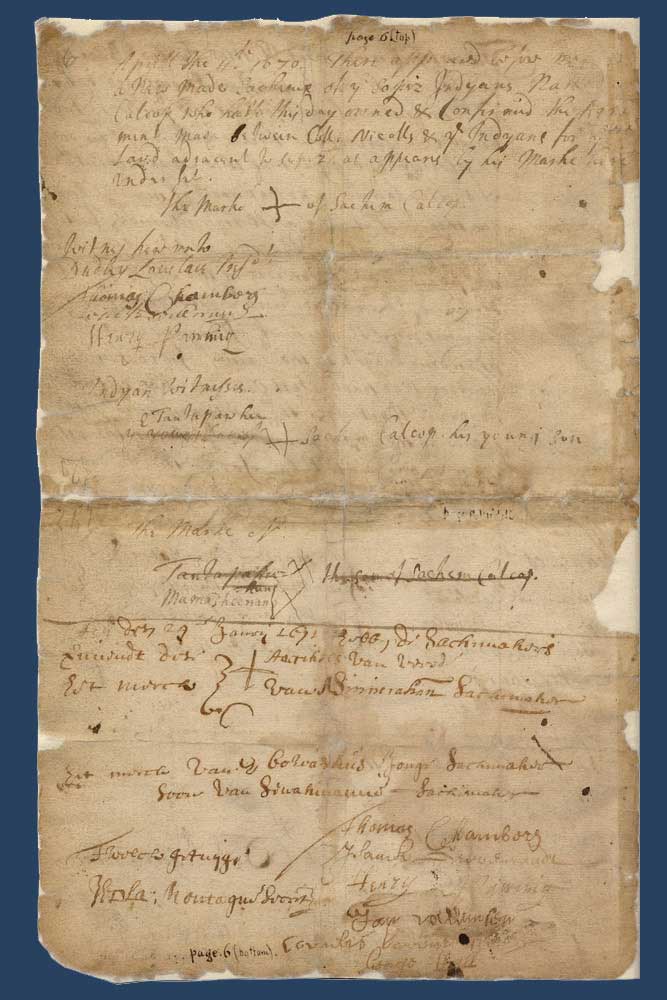

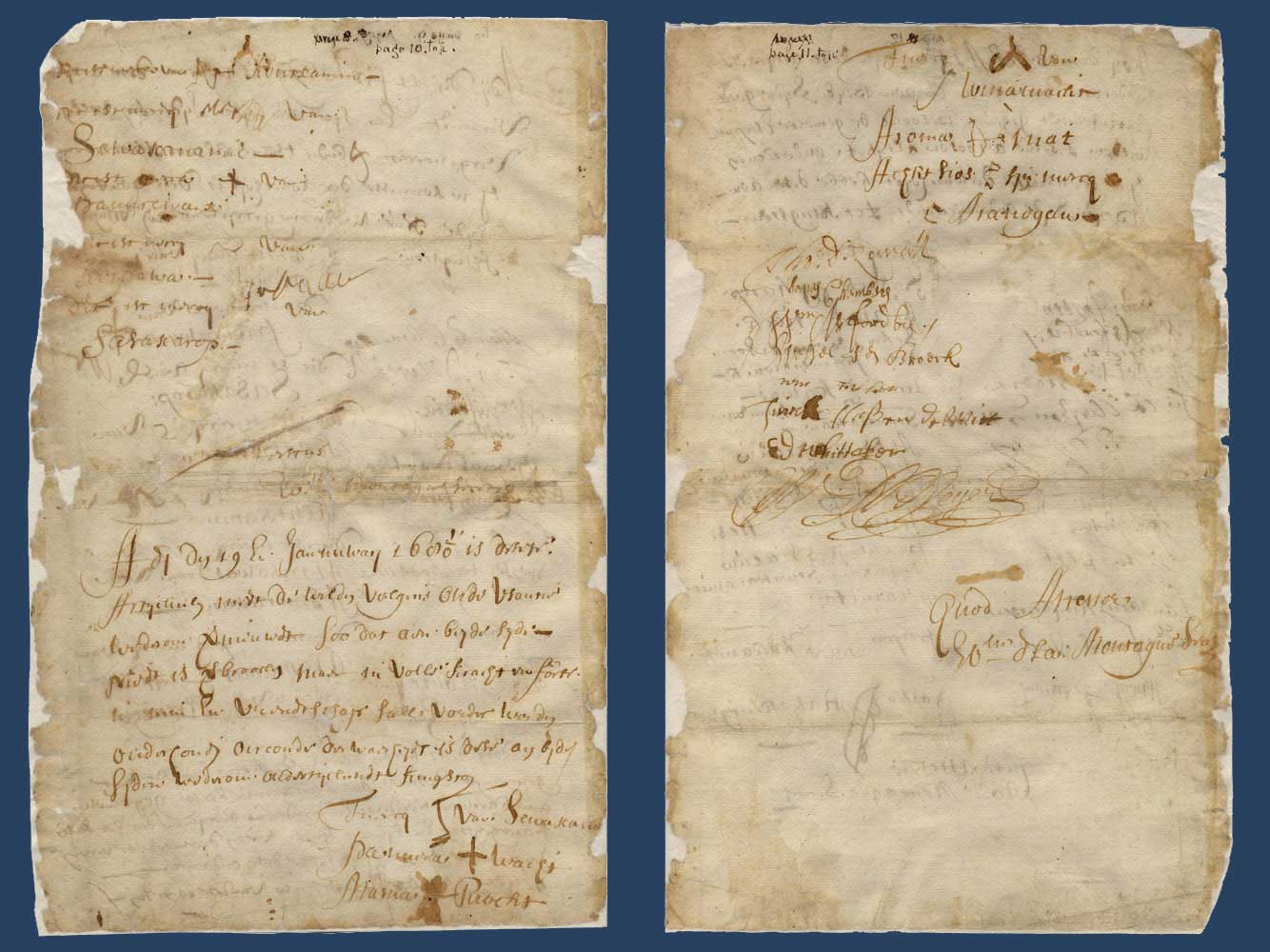

1670 and 1671 Treaty Renewals

In the 1670 Treaty Renewal, we find a new Sachem who is signing the Peace Treaty. His name is Calcop. Also, you will see that the 1670 Treaty Renewal is in English, while the 1671 Treaty Renewal is in Dutch.

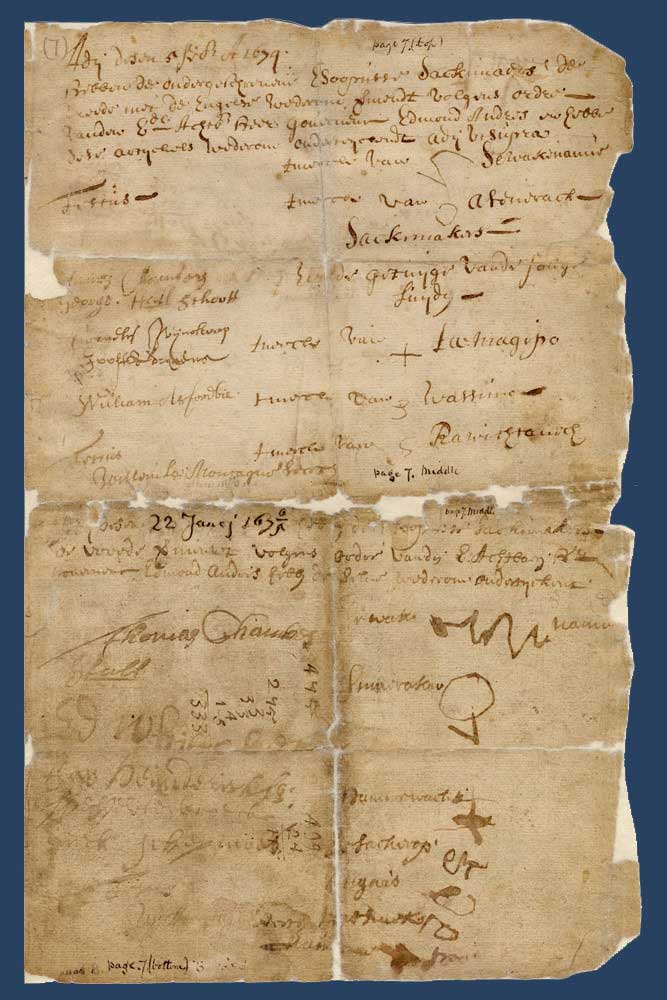

1674 and 1675-6 Treaty Renewals

In the 1674 and the 1675-6 Treaty Renewals, we see that there is a new Governor of New York, Sir Edmund Andros. Edmund Andros served as Governor of New York from 1674 to 1683.

1677-8 Treaty Renewals

It is interesting to note that, for the 1677-8 Treaty Renewals, both of these separate renewals happen in the same month. It is curious why this was done. Also, as you can see, this page was originally written upside down. You will also find the first mention of sewan or wampum being given during the renewal process.

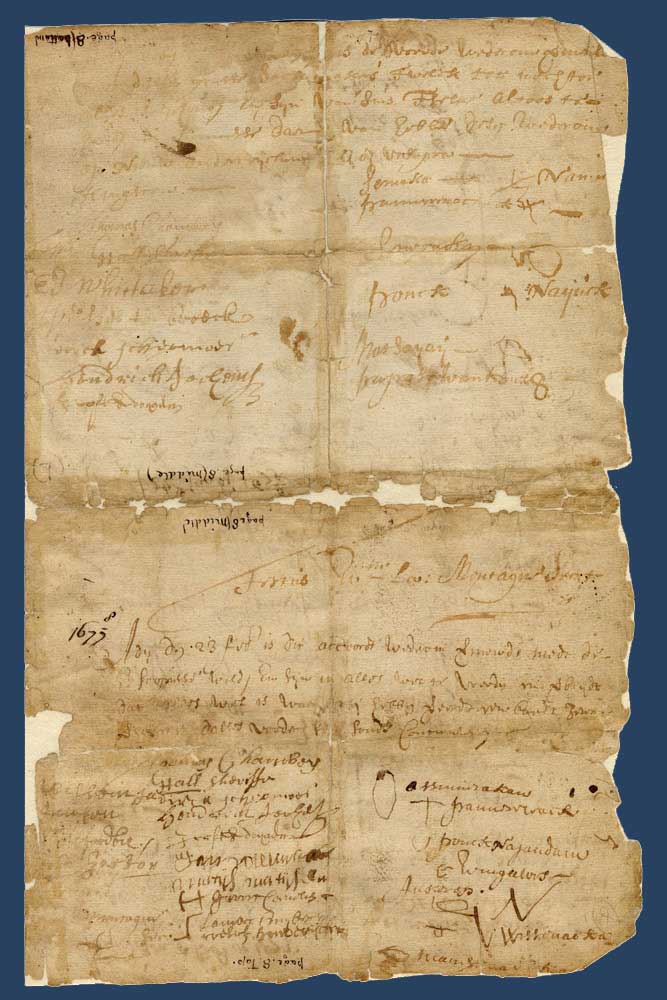

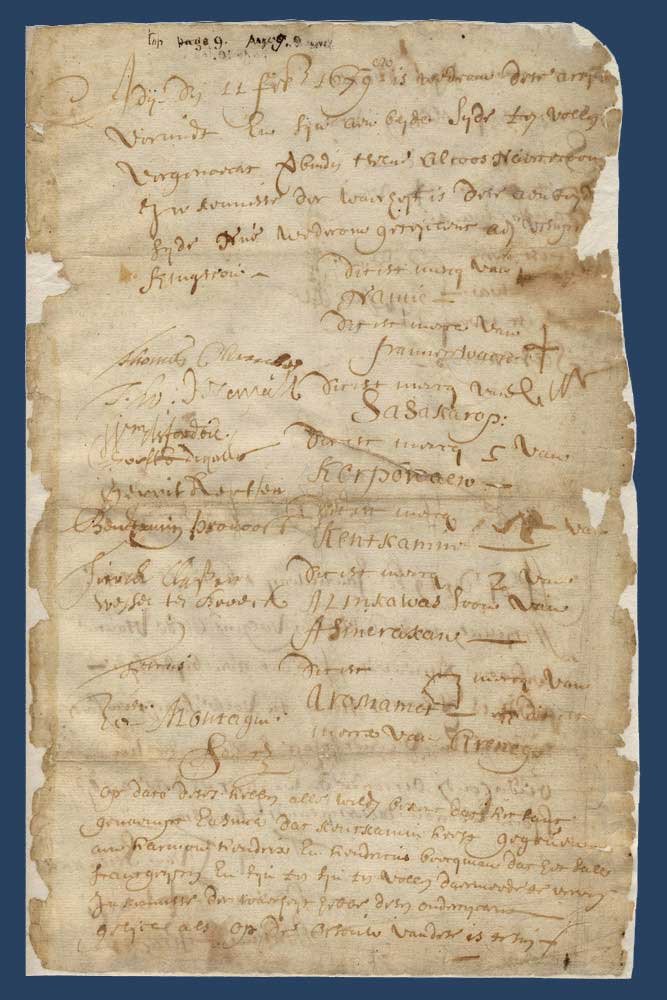

1678-9 Treaty Renewal

In the 1678-9 Treaty Renewal we continue to see new signatures and new marks, as well as familiar signatures and marks. In this Treaty Renewal, in addition to affirming the original articles, there is also a land conveyance for a parcel of land called Easinck.

January 1681 Treaty Renewal

In the January 1681 Treaty Renewal, we find striking language about friendship. It reads, “The articles, according to the old practice, are again renewed, so that they are not broken by either side, but remain in full force to bind them in continued friendship.”

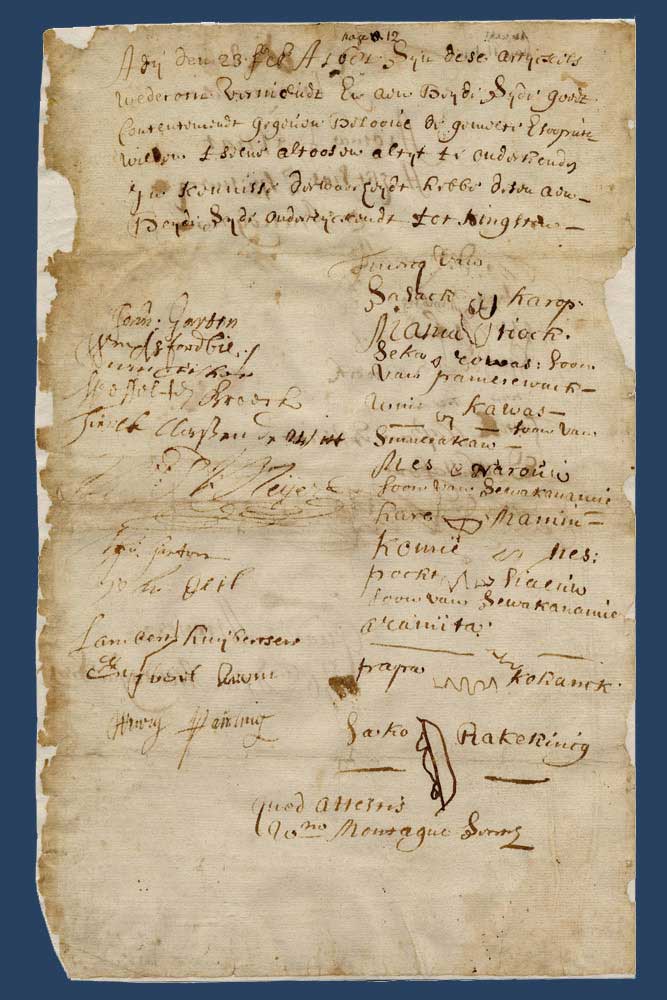

February 1681 Treaty Renewal

The February 1681 Treaty Renewal is the last renewal that was physically bound with the original Treaty. Here in this Treaty Renewal we find a long list of signatures and marks of prominent individuals. They agree that this renewal will “remain in full force to bind them in continued friendship.”

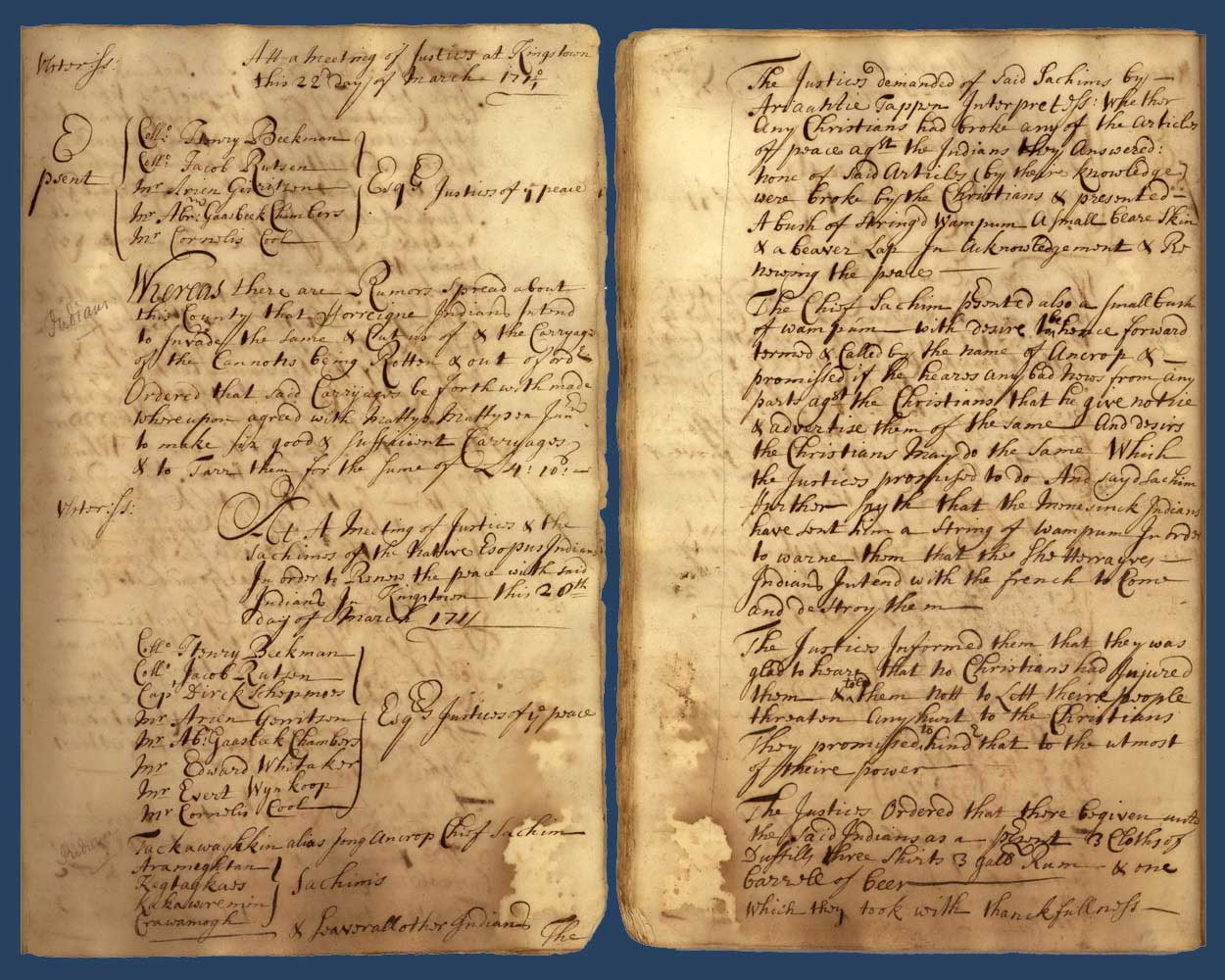

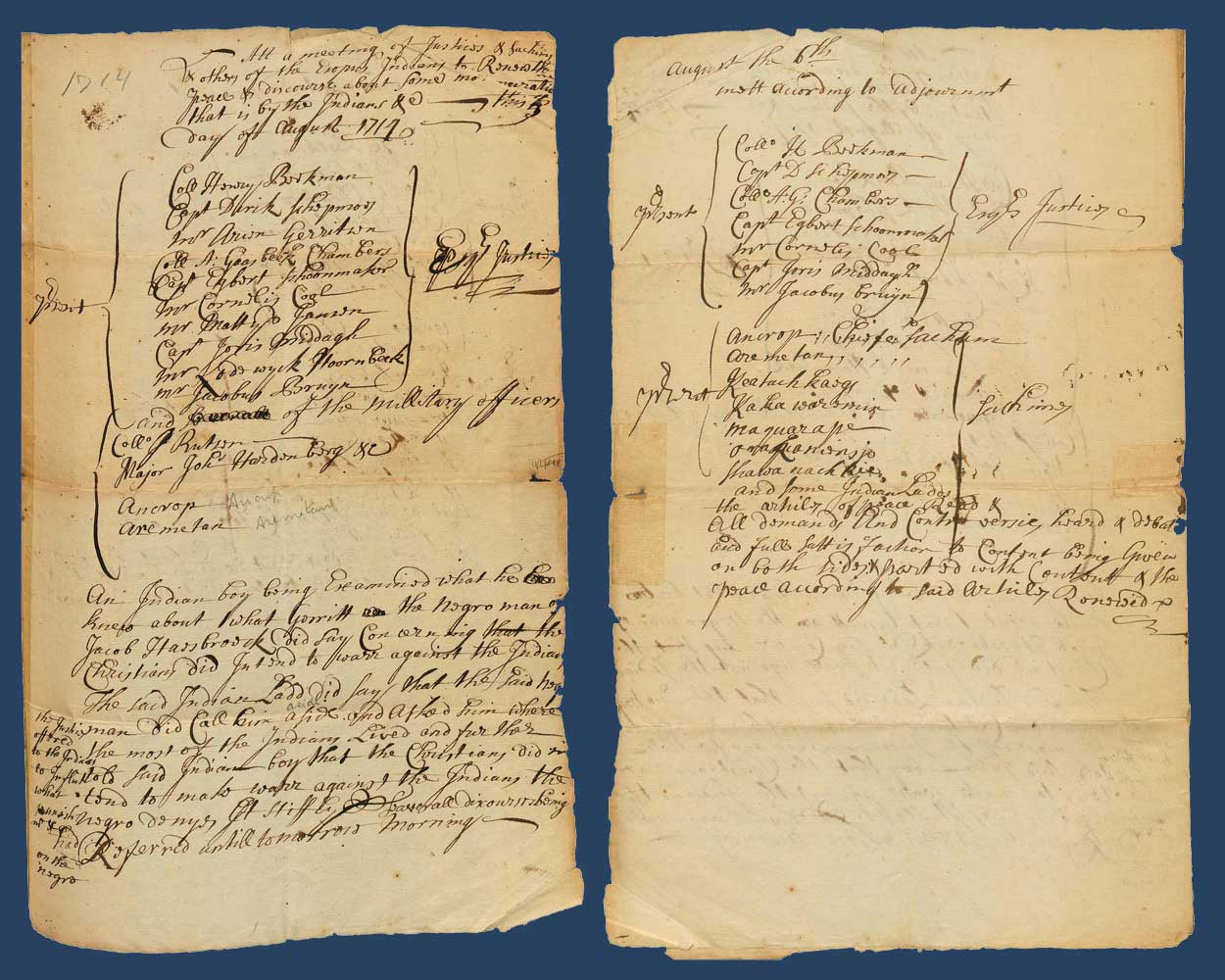

1711 Treaty Renewal

In the 1711 Treaty Renewal, we find out there are rumors of war and that the French mean to attack the Esopus Native Americans. We also see wampum being exchanged during the treaty renewal process.

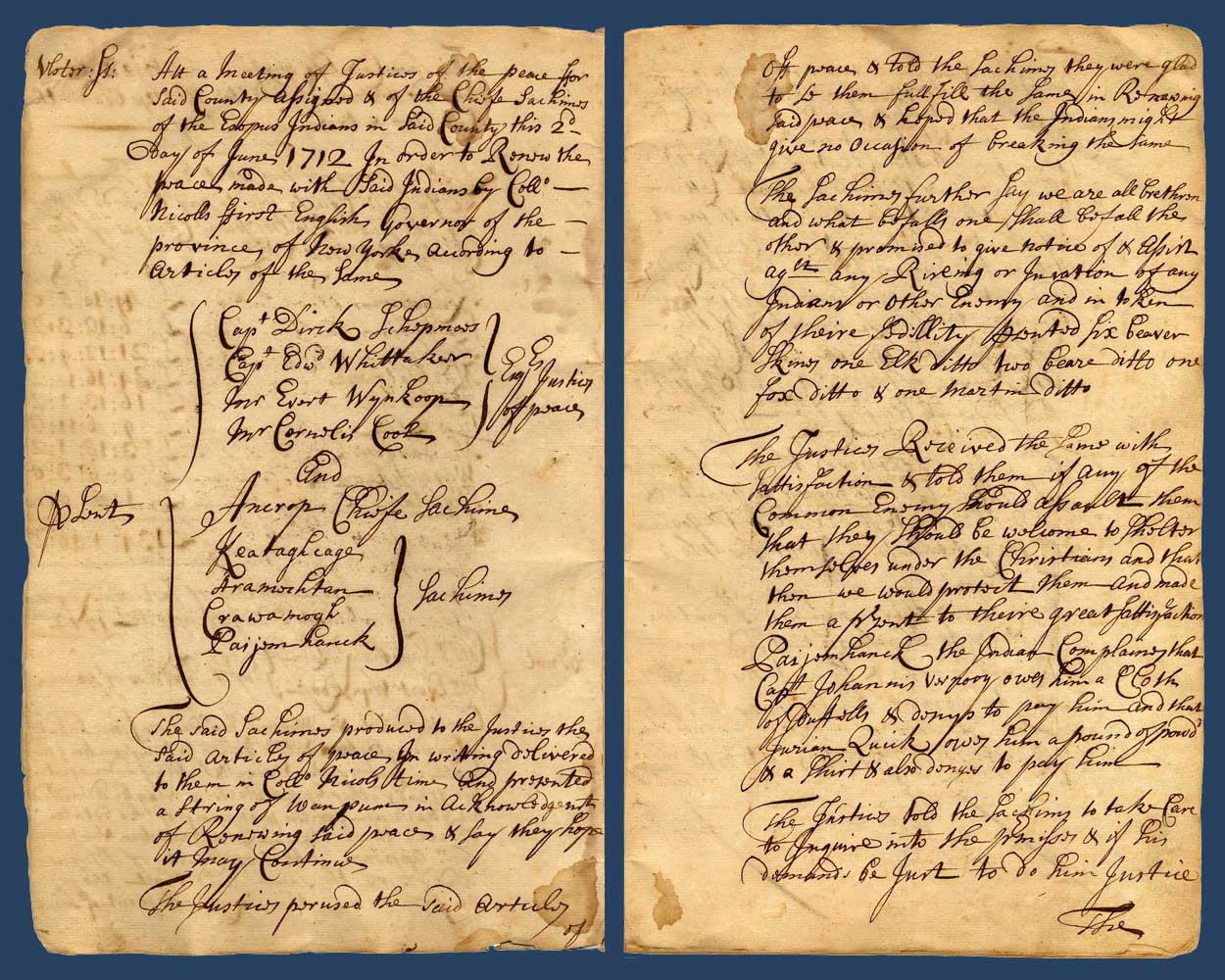

1712 Treaty Renewal

In the 1712 Treaty Renewal, we continue to find compelling words of friendship being used. Here, we find the phrase, “The Sachims further say we are all brethren and what befalls one Shall befall the other.” We also see that the Esopus still have their copy of the Peace Treaty, signed in 1665!

1714 Treaty Renewal

In the 1714 Treaty Renewal we see that the Esopus have come into court because they are hearing rumors that the Christians mean to attack them. The justices resolve the rumors and the articles of peace are again renewed.

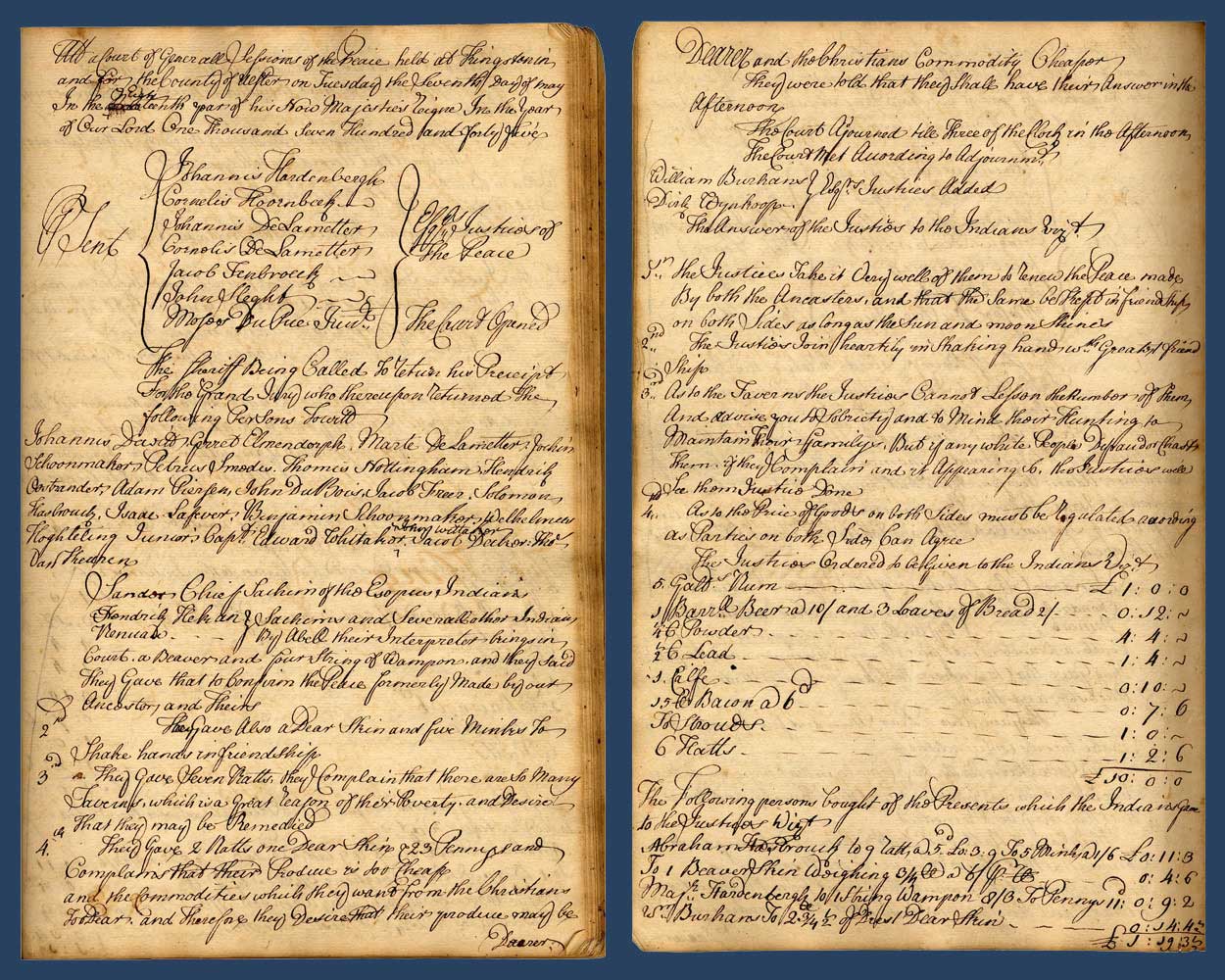

1745 Treaty Renewal

Here, we find the last of the thirteen renewals that have been discovered. The 1745 Renewal states the desire that this Treaty be kept in perpetual memory when it states, “The Justices take it very well of them to renew the peace made by both the ancesters, and that the same be kept in friendship on both sides as long as the sun and moon shines.”

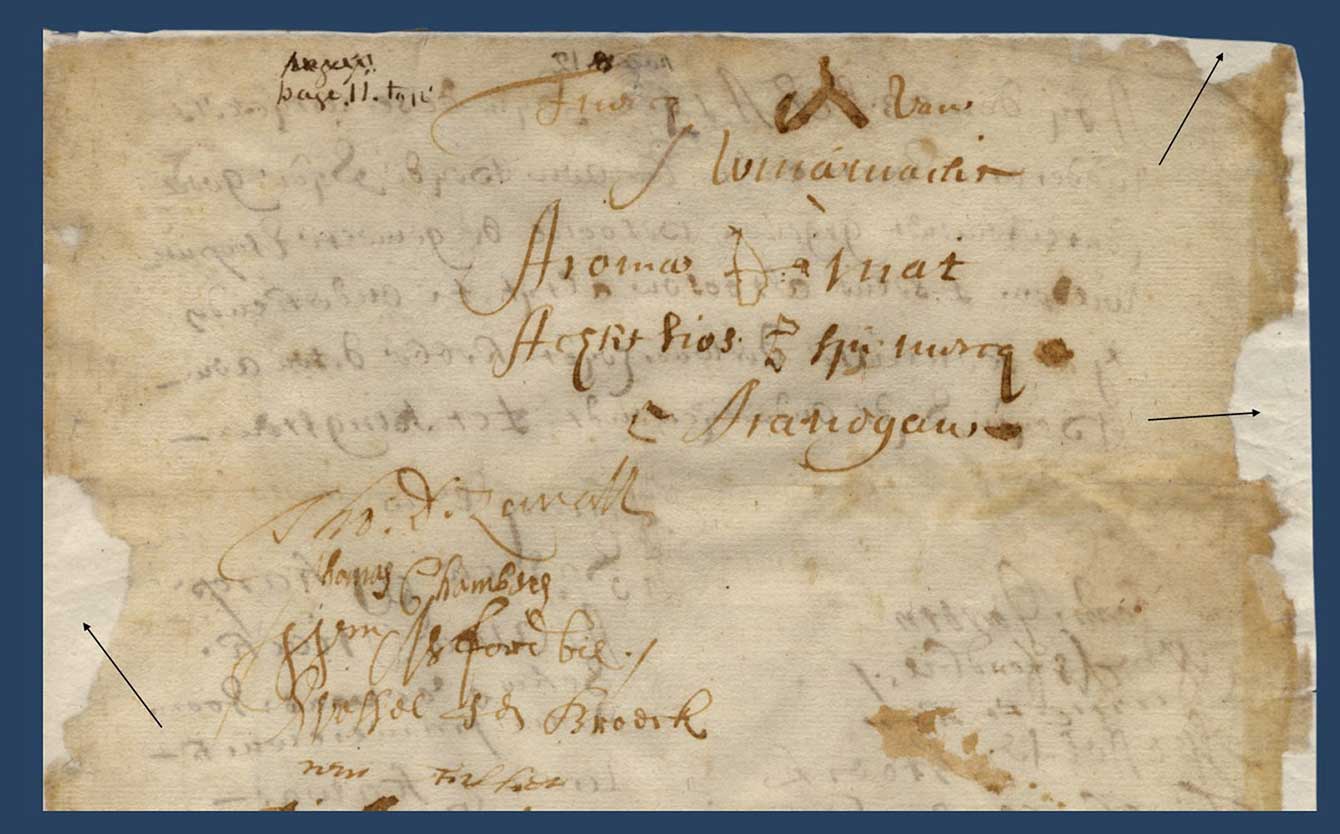

Condition and Conservation of the Treaty and Renewals

The physical Treaty record is a small handwritten folio with sewn binding. It measures about thirteen inches by eight and one-half inches and contains twelve pages. The document is accompanied by a handwritten transcription dated 1875 and stored in a drop-spine box. Both are in excellent condition. They were treated and conserved by the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) in 2002 funded by a Local Government Records Management Improvement Fund (LGRMIF) grant from the New York State Archives to the Ulster County Clerk’s Office.

The image above is the top portion of page 11 of the 1665 Treaty. The lighter paper around the edge of the original document (indicated by the arrows) is Japanese Kozo paper. Japanese Kozo paper, made from the bark of the kozo (mulberry) bush, is used by conservationists to repair tears in documents and books and fill in for any losses. A loss is any portion of a page that is missing, which most commonly occurs around the edges or increases where the page may have been previously folded.

This is the condition report written on the receipt from NEDCC:

“The treaty consisted of six previously bound loose leaves with entries in manuscript ink. The leaves were dirty, discolored and stained. The leaves were folded, broken along the folds, and crudely mended. The leaves were torn along the folds and edges, and there were some losses. A paper guard adhered to the edge of the last leaf was a remnant of previous binding. Some of the numerous manuscript inks present were faint and varied in intensity. During treatment, the volumes were microfilmed. The pH of the treaty recorded before and after treatment was 6; of the transcript, 5. The volumes were collated and disbound. The inks were tested for solubility. The pages were dry cleaned where necessary; the pages of the treaty were washed in a 30% ethanol and water solution; the transcript nonaqueously buffered (deacidified) with methoxy-magnesium methyl carbonate solution. Tears were mended and folds guarded where necessary with Japanese kozo paper and wheat starch paste. Leaves of the treaty were leafcast with Japanese kozo paper and wheat starch paste. Each volume was sewn with linen thread into a fold of paper. And finally, the volumes were housed in a drop-spine box.”

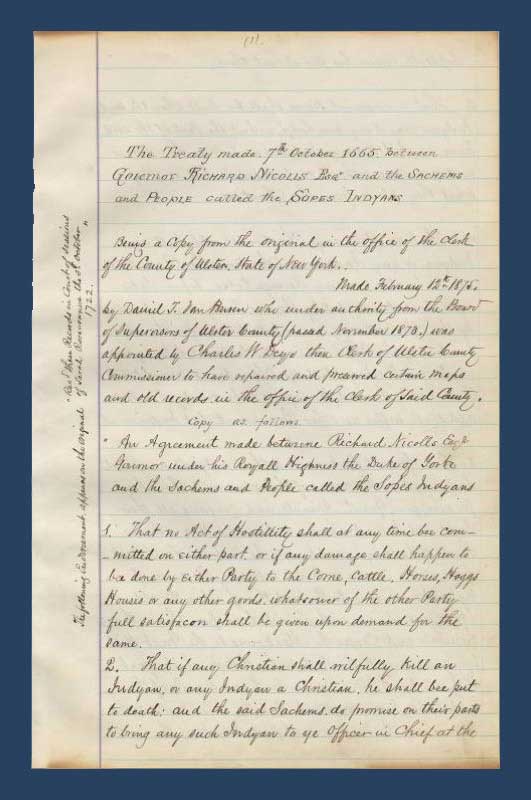

Conservation of the 1875 Transcription

Also stored with the original Treaty and Renewals was a handwritten transcription, done by Daniel T. Van Buren on February 12, 1875. Mr. Van Buren had been appointed by County Clerk Charles W. Deyo “to have repaired and preserved certain maps and old records in the office of the Clerk of said County.” While the document was in very poor condition then, it can be assumed that without Mr. Van Buren’s efforts it may not have survived. This is a good example of 19th century records management. Shown here is the first page of Mr. Van Buren’s transcription of the Nicolls/Esopus Peace Treaty.

Reformatting and Outreach

An important aspect of conservation is making the original available for use in a reformatted medium. To meet this goal, the Ulster County Clerk’s Office has produced the publication, The Treaty between Governor Richard Nicolls and the Sachems and People called the Sopes Indyans made 7th October 1665. This publication features high-quality reproductions of the 1665 Treaty, and the thirteen Renewals. Associated with each image is a transcription of the document. There is also an essay on the historical context of the Nicolls/Esopus Peace Treaty, a glossary of unfamiliar terms, and a bibliography.

Native American Wampum Belt

Shown above is the Wampum Belt located in the Ulster County Clerk’s Archival Collection. As you may have noticed, wampum (or sewan) is mentioned several times throughout the Renewals. It held great significance to Native Americans throughout the region.

Local historians Marc B. Fried and Marius Schoonmaker have associated this belt with peace agreements between Native Americans and the Dutch on May 15, 1664 at New Amsterdam, and between Native Americans and the English on October 7, 1665. However, it is unclear with which treaty this specific belt is associated. The Wampum Belt has been in the custody of the Ulster County Clerk’s Office since 1732, as per an order of the Court of Sessions. Currently, the belt is stored in the Ulster County Clerk’s Office Archival Collection.

Several years ago, a replica of the original belt was made by Waaban Aki Crafting located in Vernon, Connecticut. The creation of this replica was commissioned by the County Clerk in an effort to make the Wampum Belt more accessible to the public. Due to the historical significance of the Wampum Belt and its need for special handling, the replica serves as a symbol of the original and has been displayed all around Ulster County at different museums, libraries and events.

The professional archival description of the Wampum Belt is rather technical. However, it provides a more in depth look at this historical artifact by providing detail that may not be apparent to the casual viewer.

“A belt of braided thistle and beads, 2" x 30" x 1/4". The braided thistle is straw colored, of seven rows gathered at the ends in two knots. The beads are cylindrical in shape, white and purple in color, and form six rows. They are arranged at right angles to the strands of twine. Some sections of the purple beads appear to be missing. The purple beads form diagonal stripes on a white bead background.

The belt is mounted by thread to a linen background and surrounded by a double thick white archival mat about two inches wide. The belt and mat are enclosed in a plain black frame under glass. The overall dimensions of the framed object are 10 1/2" x 39 1/4" x 1/2". The back is covered by an off-white board and sealed with wide black tape. Notes in pencil ... are a calculation of sorts reading ‘598 beads x 10/5,980’.”

The close-up images are of the Neyuheruke wampum, courtesy of the Joyner Library at East Carolina University. They show the color variations of each bead, making them all unique and purposefully crafted.

Wampum

The following is a general description of wampum from Noah T. Clarke’s “The Wampum Belt Collection of the New York State Museum” dated 1931.

"The name 'wampum' is a term which the early New England colonists derived from the Algonkian name 'wampomeag,' meaning 'a string' (of shell beads). Indians were attracted to the use of shells in their personal adornment by their natural beauty. On account of their thin, sharp edges, shells were brought into service as implements and utensils such as cups, spoons, scrapers, digging tools and knives.

“Shell beads were the handiwork of the woman, whose skillful hands were accustomed to the delicate and tedious operation of their manufacture. Wampum beads are small cylindrical shell beads which measure about a quarter of an inch in length and one-eighth of an inch in diameter. They were wrought from various species of shells, but those made in the eastern section of the United States were cut from those found along the Atlantic sea coast.......besides their use as necklaces and for purposes of exchange, [they] were used in strings in public transactions of various nature and significance. Strung in different order or color combinations, they conveyed or recorded a definite idea or thought, which could be interpreted without confusion. White beads used alone in ritual or ceremonies conveyed the idea of peace, health and harmony; the dark or purple beads used alone in ceremonies denoted the idea of sorrow, death, mourning and hostility."

The quahog clam (pictured left) is found primarily in the coastal waters of the northeastern United States. Its distinctive shell was used to make purple wampum.

The whelk shell (pictured right) was used to make white wampum beads. The hard, brittle shells made crafting beads a difficult and time-consuming process.

Photo Credit: Smithsonian/NMAI/Stephen Lang Photography - Wampum beads

Conclusion

From 1665, when the Peace Treaty was first signed, to 1745, the date of the last renewal, and beyond, much would happen to the residents of the Hudson Valley. Life would continue to change for New York’s Dutch inhabitants as the colony became more English through the various laws that were passed. However, the Dutch still attempted one last time to regain their lost territory. In July 1673, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, Dutch ships entered the New York Harbor and took the colony back from the English. However, victory was short-lived. In November 1674, upon the conclusion of the war, New York once more reverted back to English control. In 1683, the twelve original counties of New York State were formed in New York City. Ulster County was one of those twelve. As you can see on the map to the left entitled, “Map of the Provinces of New York and New Jersey,” Ulster County was once quite large, including parts of modern day Greene, Orange, Delaware, and Sullivan counties.

By 1688, New York was added to the Dominion of New England, which was disbanded in 1689. The Dominion of New England was an attempt by the British to consolidate colonial authority. Over the next 80 to 90 years, various small wars would be fought by people from New York, and occasionally in New York. The years from 1754-1763, just a few years after the final Treaty Renewal in 1745, would see the French and Indian War fought, diminishing France’s authority and power over northern New York territory.

The Nicolls/Esopus Peace Treaty (Page 1 pictured at right) is an important document both today, and in the 17th and 18th centuries. The peace that was negotiated was so important to the various parties that they renewed the original articles thirteen times over the course of 80 years. Through our records, we see the past come alive, and the stories of the past told again.

As we commemorated the 350th Anniversary of the Nicolls/Esopus Peace Treaty in 2015, we reflected on the spirit of peace and friendship that originally brought the parties together. Let us remember what they accomplished when they wrote in the 1681 Treaty Renewal, “The articles, according to the old practice, are again renewed, … but remain in full force to bind them in continued friendship.”

Map Image: “Map of the provinces of New York and New Jersey from topographical observations by Claude Joseph Sauthier.” Engraved and published by Matthew Albert Lotter. 1777.

THE ULSTER COUNTY RECORDS CENTER

- 300 Foxhall Avenue, Kingston, NY 12401

- archives[at]co.ulster.ny[dot]us

- (845) 340-3415

- (845) 340-3418

OPEN MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY, 9:00 AM - 4:45 PM

© 2026. THE ULSTER COUNTY CLERK’S OFFICE.